Ave, morituri te salutant

I can’t enjoy old comedy shows anymore. Having gradually lost their audience, they only entertain the zombies laughing mechanically on command, people long gone and forgottenRelated, a London widow often visited Embankment station to listen to the only surviving voice recording of her late husband, reminding commuters about the gap. Upon hearing the Transport for London wanted to phase out this old announcement, she successfully pleaded them to save a copy for her.. I indulge in more contemporary affairs instead, considering there are more pressing issues at hand. Watching documentaries and reports, following people practising the most mundane and the least extraordinary things, I often come to wonder: Why don’t they protect themselves? Do they not care? Are they maybe from another, a less plagued and carefree place? And then I remember: They are from a far place, indeed, from a near past which feels oddly distant to the present time. Ignorance is bliss. And yet their existence on magnetic disks and semiconductor loops serves as a testament for the afterworld to remind it not of the past, but, uncannily, the present.

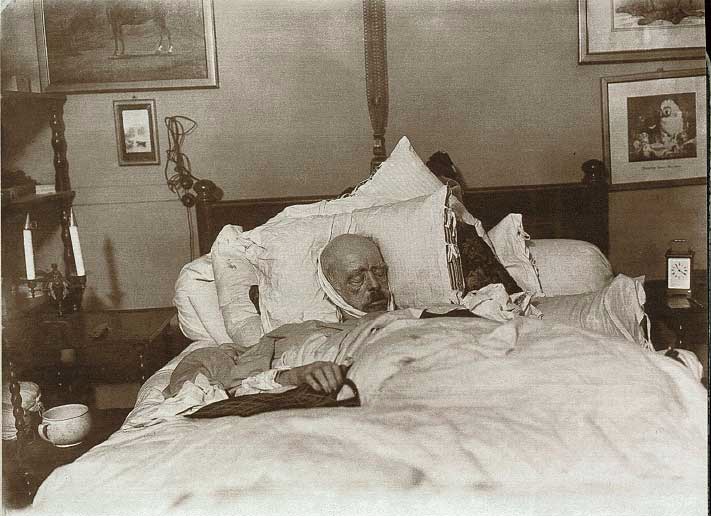

Images depict what is absent in space or time or both. And while what is dead is unbearably absent, the pictorial conservation of the deceased is not only at the core of all image making, but as often in these cases a way to give solace over this insurmountable distanceCf. Belting, Hans: An Anthropology of Images. Picture, Medium, Body. Translated by Dunlap, Thomas. Princeton 2014 [Munich 2001].. We create these lasting images – portraits, death masks, tomb stones etc. – in order to retire the corpse, for the corpse to become its own imageCf. Blanchot, Maurice: L’espace littéraire. Paris 1995. App. II “Les deux versions de l’imaginaire”, p. 268.. Or, arguably, we produce images to allow, sometimes to invite the death of the depicted in question. For each youthful Dorian Gray there is a corpse wandering this earth and for each vivid collectible card of Albus Dumbledore there is a spell cast over Hogwarts’ headmaster.

However, unless there is a personal, emotional relation to the image, it more often seems to be securely contained in the past, out of reach and safe to look at.

Watching television or videos on the web, one comes across different images. Healthy and carefree people flocking to the parks and concert halls, crowds pushing through the busy shopping streets and dancing at the clubs. These images are neither coated with the patina of technological antiquity nor do they hint to outdated fashions and customs. Save for the irregular disclaimer “shot in 2019” they do not show any sign of being of a bygone era. For all we know, they were produced only a few minutes ago.

While pictures of deceased people rarely haunt us, precisely because we know they belong to the past, the more contemporary artefacts evoke the dread and horror of being neither of the past nor the present. Riding the uncanny momentum of the passing of time, they reach out and firmly cling to our otherwise undisturbed perception of eternal presentness. In contrast, if one looks past the initial irritation, one can realise they establish a history of the now and an archaeology of the yesterday. Suddenly, when watched through this lens, a clearer view, one of ethnological proportions, becomes available: How did we go about our days? Which place had solidarity, caution, and conscientiousness in this culture? Which customs were lying dormant, waiting to become relevant and helpful again? And what was lost in the process? After all, the living dead great us. Let’s listen to what they have to tell.